What you need to understand about James Dean is, he isn’t an actor; he’s a dancer. Watch him in East of Eden (his first and greatest performance) and you’ll see him hurling his body from scene to scene. He slinks, he slithers, weaving and bobbing, leaping and lunging, flinging himself at his bible-clutching father, trying to win his love. There’s a famous shot where he rides atop a freight train, origami-ing himself into a grimy sweater, then leaping off like Baryshnikov. You’d think the director was Martha Graham, not Elia Kazan.

Dean plays Cain, (“Cal” in the picture) and it is his jealousy and confusion that fuels the rage he “slays” his brother with. He pleads with the camera, plays peak-a-boo with it, then offers himself to it like a sacrifice. He starts a climactic scene in a front yard tree swing, flying at the lens, he surges and retreats, surges and retreats. The physical action says, “I don’t give a fuck,” but his inner life screams “I care, I care, I care!”

And always there is a sexuality and sexual ambiguity. He’s a boy. He’s a man. He’s a girl. He lazes in the wildflowers, giggling with Julie Harris like a girlfriend she’s confiding in, but all the while he’s seducing her (and us) with his wild, unknowable heart. It’s the not the character’s mystery and fragility she swoons for, it’s Jimmy’s. He vibrates at a different frequency and this vibration becomes the story. He writes the script with his body, his movement, and that face. The nose may be straight, but there’s something crooked about that boy. He’s the alien from Indiana. Sometimes he’s just eyebrows on top of an achingly tender mouth; then he turns to profile and becomes a pompadour with a small, angelic chin. The beauty is both classical and unusual. The combination of old soul wisdom and delicacy, disorienting. He’s androgynous, but not as an artistic choice. The gender battle (or more accurately, gender union) is psychic and within.

My desire to get into the “Jimmy” of it all stems from a road trip I took up to Paso Robles. I went past the junction of Rt. 46 and Rt. 33, the hunk of asphalt he made famous seventy years ago. That was 1955 and Brando ruled with an iron lisp. But if Brando was king, James Dean was Hamlet, and you know there must have been a little "To be or not to be" as he revved up his Porsche Spyder on that fateful September day.

They got a gas station/rest stop/store up there, and his giant, plywood image looms over the flattop. It’s the classic Dean: legs crossed at the ankle, one hand on his blue-jean hip, a cigarette in the other. He wears motorcycle boots, the cranberry windbreaker over a white tee. This is the Dean we know best. Not an actor, but an icon; a celluloid Jesus, nailed to the cross of cool.

This image was formed by (or maybe victim to) a few key factors, the first of which is a movie title. If Dean’s second film had been called “Confessions of a Juvenile Delinquent” there would be no twenty-foot cutout of him in the middle of California, but it wasn’t, it was called “Rebel Without a Cause.” A great and lasting piece of American poetry. Then there’s the outfit. Maybe it was the costumer, maybe the director, maybe it was Dean himself, but whoever decided on that cranberry windbreaker was a genius. A black leather jacket would have had a completely different meaning, but Dean isn’t a villain, he’s the bad boy equivalent of a hooker with a heart of gold. The red softens him. He doesn’t just wear his heart on his sleeve, he wears it on both sleeves and across his back. Another factor is his name. James Dean is just a cool fucking name. Two syllables; the first reaching for the second, the second gone before you know it. And lastly, of course, there is the way he died. He’s our Icarus; the wax wings swapped out for a racing car. Forget the “27” club, he’s dead at twenty-four! And unlike Brando there are no second-rate James Dean movies, no Dean gets fat in his forties, no slow and sad demise. Just a flash of light and the light put out.

I got some gas, and walked through the store. It was a knick-knack onslaught, Jimmy’s image emblazoned on buttons, whisky flasks, even votive candles. (Who wants a key chain with a picture of a guy who died in a car crash?) As I pay for my pistachios something catches my eye. It’s a black, soft-cover photo-book, put out by a Japanese publisher. (If anyone knows how to worship the fetish object, it’s the Japanese.)

The book is called “The Memory of The Last 85 Days.” The photos are by Sanford Roth, a famous mid-century portraitist, who shot Einstein, Cocteau, Picasso, Matisse, Stravisnky, Tennessee Williams and every famous movie star of the era. Roth took pictures of Dean on the set of Giant and they quickly became close, Dean treating he and his wife like adoptive parents. Roth was driving behind in Dean’s station wagon when Jimmy crashed, and took the famous pictures of the mangled car.

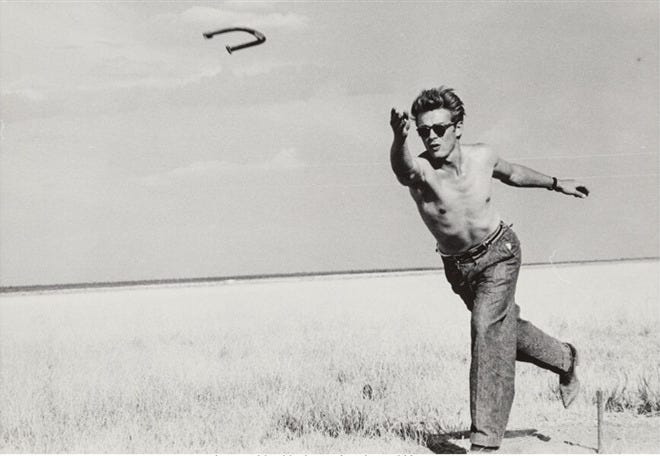

I start thumbing through the book and it blows my mind. Not because he’s so photogenic and incredible looking (which he is), but because the person in the photographs has absolutely nothing to do with the huge plywood cutout in the parking lot. The cutout is a live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse Hollywood creation, but the man in the photos is a goofy, playful, glasses-wearing art boy. Vibrant, expressive and wildly alive, he is too close to the source for the God’s liking, and so, like Cain, they banish him to the land of Nod.

Alright, maybe I’m getting a little carried away, but that’s because he carries you away. He’s so much more than an icon of angsty teenage cool. Whether communing with the Roths’ cat in a striped shirt, or sculpting intently, a Lucky Strike dangling from his lips, or stripped to the waist, washing his Porsche like a doting father, you feel his soul in all its tangle. His aching, complicated joy.

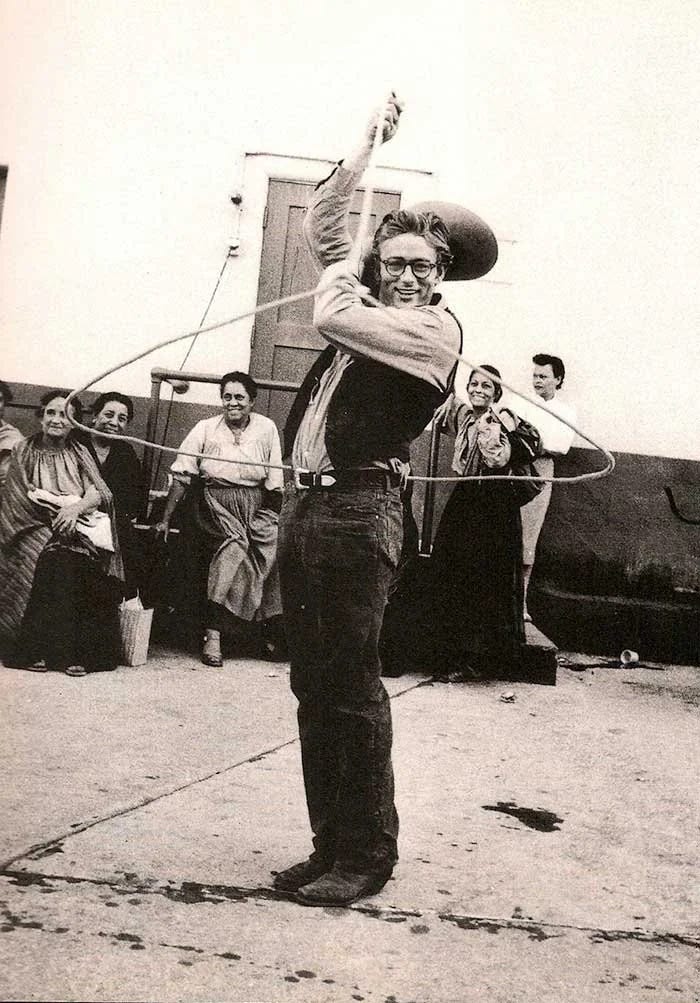

My favorite shot is one of him on the set of Giant. He’s goofing around, standing inside a spinning lariat like the nucleus of an atom, a group of female Mexican extras in the background. It’s the look on his face that gets me, the bookish glasses and all that dimpled joy, the posture halfway to Flamenco. Whatever “it” is he’s got his own special batch, which is why he will always be remembered—Just not for who he really was.

Toward the end of East of Eden, Dean proudly offers his father a fistful of money he’s made investing in beans. The money is to cover losses his father suffered earlier, but his dad will not take it, no matter how much Dean pleads. This rejection crumbles him and moaning his grief, he drapes his arms over his father’s shoulders like a lover, their faces now inches apart. For a moment it seems he might kiss him on the mouth, but instead, he grips him desperately, sobbing on father’s chest. It is a wild, risky choice, both male and female. But the pronoun is not “they.” The pronoun is James Dean.

Tommy's contention that James Dean is more of a dancer than an actor because of the striking, mesmeric way he moves about the big screen is compellingly argued in this excellent essay. But even so, Dean's considerable skills as an actor are not ignored. I particularly like this paragraph, which I think captures the essence of him very well:

"He’s so much more than an icon of angsty teenage cool. Whether communing with the Roths’ cat in a striped shirt, or sculpting intently, a Lucky Strike dangling from his lips, or stripped to the waist, washing his Porsche like a doting father, you feel his soul in all its tangle. His aching, complicated joy."

Reminds me of a similar swaying man of the swinging 60s in India - Shammi Kapoor. Most actors do not know what to do with their hands. He choreographed his moves while sitting on a boat or a chair - the woman had to blush away. Shammi looked a lot like Elvis.

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/6b/86/a7/6b86a721e237bf921b776d3c30cf8b7f.jpg